Will Steffen, 1947-2023

Last week humanity and the planet lost a towering figure, a person who has taken huge strides to warn us of the dangerous pressure human activities are putting on the Earth system

This past week brought the sad news of the death of Will Steffen, a brilliant climate and Earth scientist from Australia. Unless you’ve been following climate science for quite some time you may not have heard of Steffen. But you will surely be aware of several terms closely associated with Steffen and his work. He was working hard scientifically, and by communicating, to preserve our planet and everything on it.

I’m not sure where I was, some years ago, when a scientist during a research talk put up a slide which shocked me profoundly. It was all I thought about for the rest of the day; I have never forgotten it. That scientist credited the slide to Steffen, who had over many years been accumulating empirical evidence on the rapid rise of the scale of human impacts on essentially every aspect of our planet.

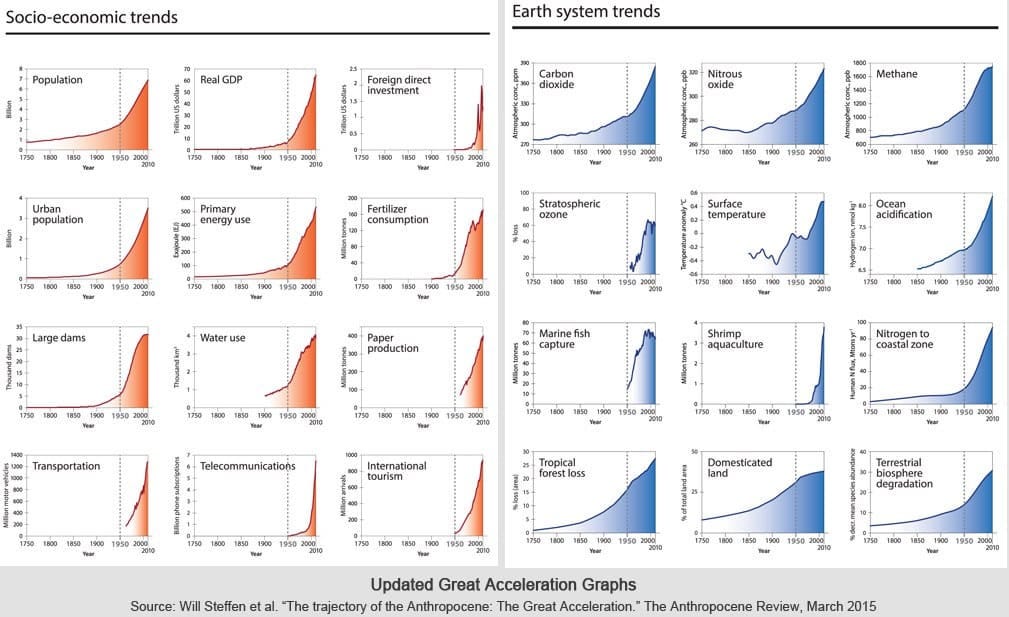

You can see a version of the slide below, which Steffen eventually sent to me after I contacted him by email. As far as I understand, he updated this slide systematically over many years. I include it here so readers will perhaps feel the same sense of dread I did when I first saw the slide, and started to appreciate the awesome story it tells about the current state of our planet.

What you see is 24 different quantities, some from the human world, some from the physical world, reflecting how our world has changed since 1750 or so. A certain worrying trend is obvious.

As the slide shows, all of these impacts have been gradually growing, but after 1950 or so something dramatic has happened on Earth. On any measure considered, the scale of human impact has risen dramatically. It is probably no coincidence that this is precisely in the post-WWII era during which economists came to the view — as detailed in an article I wrote last year for Bloomberg — that there should be no limits to economic growth, despite the finite size of the planet, because growth comes from human innovation and need not in principle place any burden on the planet.

The history behind this view is somewhat interesting, as I learned from a discussion with the distinguished University of Cambridge economist Partha Dasgupta. As I wrote in that article,

An early growth theory, proposed by economist Robert Solow in 1948, held that long-run growth depends on basic factors including population growth, saving and investment, and the rate of technological development. Later growth theories have essentially followed this plan, emphasizing technological innovation — our ability to continually find new ways to use resources more productively — as the real engine of economic growth.

Dasgupta pointed to this deep faith in innovation — drummed into economists by what they saw happening in the postwar era — as the reason economists of the 1970s rejected suggestions by natural scientists that there might be natural limits to growth. These scientists suggested that the human expansion of economic activity would eventually grow too large for the planet to safely contain; that our activities could undermine much of the value that is produced by the natural world. Economists dismissed these worries, believing that innovation would always allow humans to find a way around such problems.

The early growth theorists — not by intention, but through some subtle assumptions they made — effectively stipulated that nature has no important role in supporting economic growth. In the standard theory, human innovation enters the growth formula as a purely human construct, not dependent on a huge range of valuable things the environment provides for us, like clean air and water, a stable climate and plentiful reservoirs of complex bio-matter. As a result, innovation, and growth, are always possible, even if the natural world were to be severely degraded.

This seems like a huge oversight today, when the science of ecology has been well-developed and we’ve got decades of evidence showing the natural costs of human activities.

Indeed, this view which sees no natural limits to growth has played a huge role in justifying the ever-increasing extraction of resources and enlisting of global planetary processes for the satisfaction of human needs, despite the costs to the planet and all other organisms on it.

** [As an aside, I should say, I’ve always harbored a certain animosity against economists for this view, and seen the neo-classical growth theory as an assertion of incredible arrogance. My discussion with Dasgupta has convinced me this isn’t quite the case. The history of how we got stuck here, at least the academic history, is more a case of ordinary research going horribly awry, and brains getting bound up in a bad place. A few simple assumptions, followed to their conclusion in an era of apparent easy growth and spreading wealth, which bolstered confidence, have led to awful outcomes.

However, it does point to a deep failing of economics to have shielded itself from physical reality and ecology for so long. They did in the 1970s, the 1990s, and 2000s. Most mainstream economists continue to do the same today. For reasons of academic pressure and taste, the word “environment”, Dasgupta said to me, cannot appear in the American Economic Review, one of the most prestigious journals.]

The Great Acceleration and the Anthropocene

In no small part due to the efforts of Will Steffen, this post-1950 period has come to be widely known as the Great Acceleration. It is an absolutely unique period in human history. If we were to condense time, including the very long history of humanity’s slow development prior to about 10,000 years ago, the last 70 years would appear something akin to a violent explosion. What has happened, in the context of history, is effectively instantaneous. We’re in the midst if it, just about to feel the consequences, but still unable to see precisely what they will be.

Will Steffen was also very involved in the recognition of this era of time as particularly special and deserving of a new name — The Anthropocene — referring to an era during which global geophysical and biological processes have been most strongly determined by human activities. This is strongly reflected in Will Steffen’s figure above.

Planetary Boundaries

If all that wasn’t enough, Steffen was also part of the group of scientists who pioneered the idea of monitoring the state of the planet through efforts to map out so-called planetary boundaries — nine particular geophysical quantities which can be checked to see if human activities have pushed the planet out of the safe environmental space in which humanity has thrived over the past 10,000 years. Below I’ve put a figure from the Stockholme Reliance Centre giving a visual assessment of the various boundaries, some of which need more research.

As you can see, in two such areas — bio-geochemical flows and ecosystem or biosphere integrity — we have already arrived in the danger zone where the best science suggests we are in an unsustainable situation.

But enough on that. Will Steffen seems to have been, like many scientists, extremely helpful to anyone interested in science, in learning more, in helping push the world in the right direction. It’s sad he’s gone, and I’m sad I never actually met him. We need more people like him.

From an article written in the Guardian:

In a hand-written letter in 2020 for a project that asked climate scientists how they felt about the future, Steffen wrote: “I’m angry because the lack of effective action on climate change, despite the wealth not only of scientific information but also of solutions to reduce emissions, has now created a climate emergency.

“The students are right. Their future is now being threatening by the greed of the wealthy fossil fuel elite, the lies of the Murdoch press, and the weakness of our political leaders. These people have no right to destroy my daughter’s future and that of her generation.”