Our failure of imagination over climate change

As the consequences of climate change mount, oil companies remain eager to pump and burn ever more oil in coming decades. It's looking like many people just can't believe the threat is real.

Today an article in The Guardian made an obvious if rather dramatic observation: the pace at which sea levels are rising threatens “a mass exodus of entire populations on a biblical scale,” in the words of the UN secretary general António Guterres. The rate of sea level rise, the article continued, is faster than it has been any time in the past 3,000 years, and threatens to displace nearly a billion people in coming decades.

A sea level rise of about 50cm by 2100 is likely, according to estimates produced by the World Meteorological Organization. That’s 50 cm in the next roughly 75 years, nearly a centimetre per year. The relentless rising of the seas is apparent in the figure below, charting the rise of global mean sea level over the past 30 years.

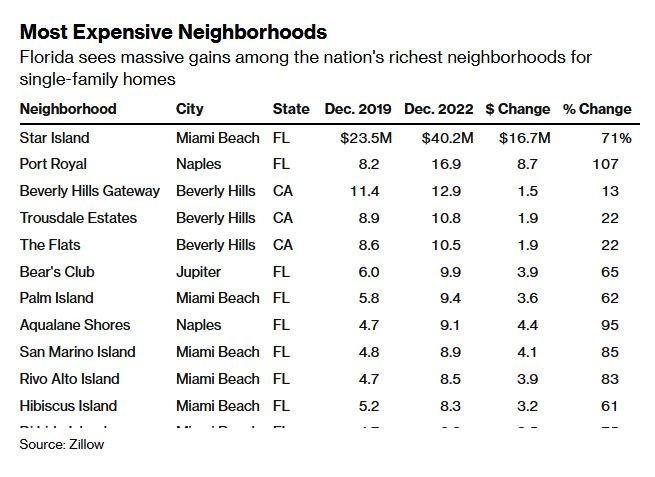

It’s certainly weird that figures like this appear routinely only a few clicks away from others showing wealthy people still flocking to invest in sea-side property, such as the one below from an article in Bloomberg showing many beach properties in Florida drawing record prices, especially around Miami Beach.

I’m sure many of these buyers believe something will happen, someone will step in, most likely the government, to raise roads, build new sea walls and so on to keep the rising waters away from their properties. Just build a big dike as they do in the Netherlands. What they forget is that South Florida rests on porous limestone, and building a wall will do virtually nothing, as the water will simply rise up from the ground well behind the wall.

And remember — 50 cm by 2100 is a conservative estimate. Quoted in the article above, Hal Wanless, chairman of the University of Miami’s geological-sciences department, reported that many geologists see the possibility of a ten-to-thirty-foot rise in the Miami area by 2100. That will be interesting.

I made a quick map from an online resource projecting levels of routine flooding (in red) under different conditions of sea level change. Under conditions of only around a meter rise, I found the following map of the Miami area, with the South Beach area essentially missing:

A lot of people are going to be on the move.

In the Guardian article, Guterres went on to observe that the coming displacement of people due to sea-level rise isn’t going to just inconvenience some rich people in Florida. Far more importantly, it will have “dramatic implications” for global peace and security, which is a relatively benign way of saying that mass global migrations of refugees from climate disaster will likely create social crises and political tensions far beyond anything we have seen in recent years.

And if anything has shocked modern political sensibilities, it is how quickly the flow of a comparatively smaller number of regugees from Libya, Syria, Afganistan and Iraq into Europe over the past 15 years has stirred the rapid rise of far right political parties and tensions between nations.

The Guardian article didn’t mention it explictly, but it is not hard to imagine that the most disruptive consequences of climate change may not be the immediate physical and biological consequences, flooding, wildfires, droughts, crop failures, and so on, but what emerges after — far-reaching social and political instability. But we rarely think about how climate change might bring on some new era of global warfare on a scale never before seen.

In this sense, our imagination seems to be failing us, as if we lack the capacity to believe deep down that the world could change, radically and quickly, on account of own collective actions. Maybe in part it’s because CO2 and other greenhouse gases are invisible. Maybe it’s because we’ve been hearing about the problem for 40 years and little in our day-to-day lives has really changed.

Unfortunately, I’ve lost the link to a recent Tweet where someone made a hugely insightful comment on this aspect of the problem. Why is the general public not yet panicking over global warming, they asked? The evidence is surely there; panic ought to be the rational response. But people in fact rarely act on their own independent assessment; we’re social organisms, and determine our actions in large part by looking to others.

And what people see today, and what they’ve seen for several decades, is that most of their leaders, politicians and prominent figures in business, aren’t panicking. Rather, their going on making ordinary decisions as if the future will end up being pretty much like the past. Seeing a world of people acting more or less normally, most of the rest of us act normally too, even though we sense it’s a big mistake.

Again, this is a lack of imagination. The weird situation reminds me of a fascinating nonfiction work I read five years ago. In “The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable,” novelist Amitav Ghosh explores his own puzzlement over why there is so little modern fiction which focusses on climate change and our inadequate human response to it. Why the silence on such an important matter?

The reason, Ghosh concludes, is that the literary world today largely sees the aim of serious fiction as exploring individual human experience and moral struggle. Artists largely ignore climate change, he thinks, because it’s just too hard to believe, its extremes too far-fetched and terrifying to seem plausible.

So novelists are, in a sense, “deranged” — the specific word Ghosh uses. We are, he thinks, imaginatively impaired by the climate issue, which seems somehow otherworldly and unnatural. And of course it’s not only artists. Most of us share this inability to tangibly comprehend the astonishing future to which the scientific evidence points, thereby ensuring indecision and lack of action. Many of us claim we want a different world yet also go on acting in a way that keeps the world as it is.

As do the fossil fuel companies, as this past week brought the news that the big three firms — BP, Shell, and ExxonMobil — have all abruptly changed their plans about trying to reduce emissions and support a shift to a low carbon economy. Instead, all three are now planning to push forward with aggressive moves to find and extract more gas and oil. Wonderful.