Can the law save us over climate change?

A surge of new legal cases is putting governments and corporations under intense pressure over their response to global warming

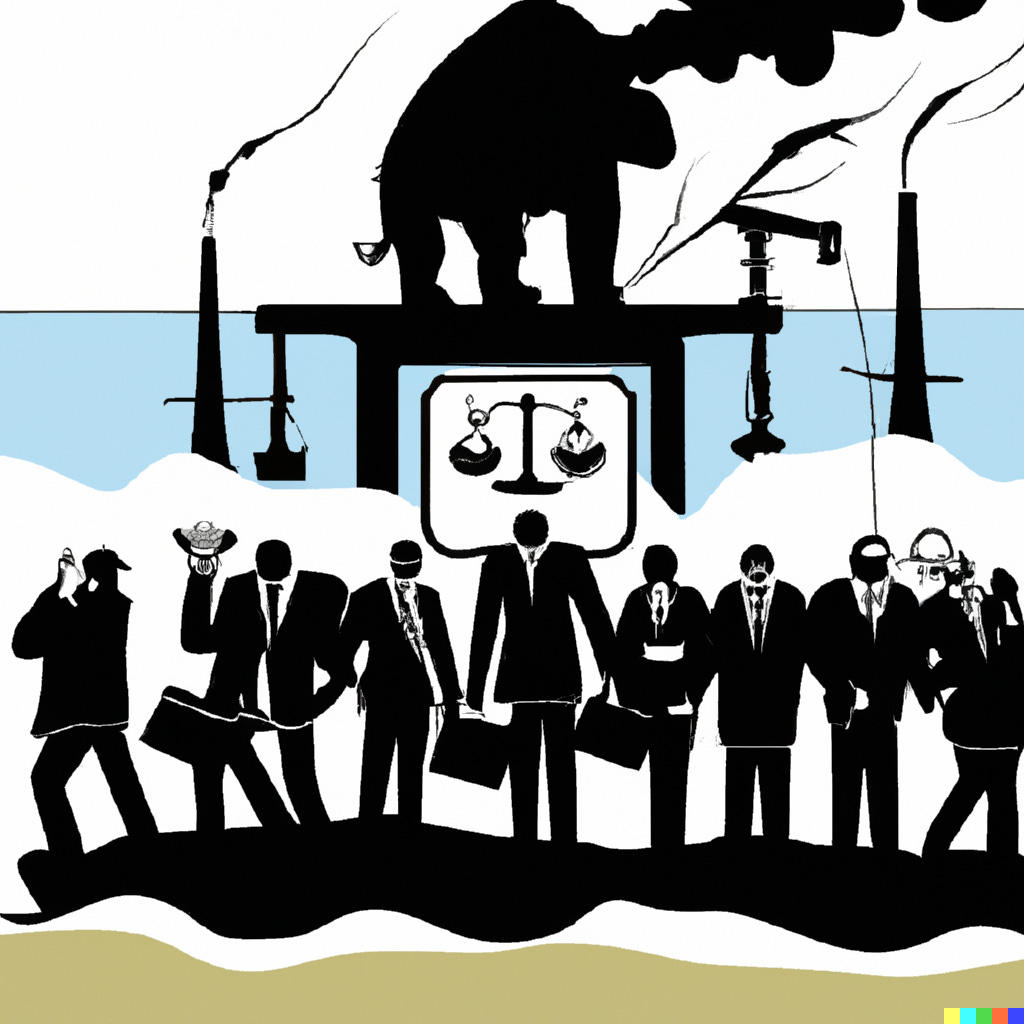

The emphasis on darkness in the image above is appropriate, as the recent news about global warming and climate change is pretty depressing. A study published two weeks ago found that scientists at Exxon had an astonishingly clear understanding of the likely global climatic toll of CO2 emissions as long ago as the 1970s, yet company executives still denied these facts in public for decades — just to preserve the company’s profits. Planning for the COP28 meeting scheduled for November 2023 entered into the absurd when the host United Arab Emirates appointed the CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company to head up the climate talks.

And this is just the news of recent human inaction over the climate crisis. The scientific outlook is worse. The latest update from the University of Columbia’s James Hansen observes that the planet’s climate has actually benefited over the past five years from a significant cooling effect due to atmospheric pollutants, especially in China, which have been reflecting sunlight back to space. Chinese progress on cleaning up that pollution (obviously, a good thing) is eroding that cooling effect, which means the warming from greenhouse gases should become even more apparent.

Among other things, Hansen and colleagues conclude that these changes have nearly doubled the net energy imbalance of the Earth over the past decade. Interestingly — and I didn’t know this — he notes that this quantity fluctuates significantly from year to year due to changes in things like cloud cover and other related atmospheric dynamics. But he and colleagues offer the tentative conclusion that the increased energy imbalance will likely cause an acceleration of global warming by as much as 50-100% in the few decades.

OK, but how about something more positive? If there is one hopeful trend, as I’ve recently been exploring, it is in efforts to use the law to start holding governments and corporations to account. Or, at the very least, to make their continued inaction increasingly costly.

The legal angle

I wrote a short piece for Bloomberg last year on the changing science of climate attribution — the science of linking damaging climate outcomes to prior emissions in a causal way, which is necessary if parties suffering damages can seek financial compensation. The science of attribution is itself fascinating. If I can just quote a short part of that article,

“Attribution” — the term scientists use to describe the evidence linking human behavior to global warming — isn’t as easy as it might seem. Proving that some flood or storm damage is due to climate change, and not just a freak event of normal weather, means showing that such an event would have been much more unlikely in a world in which climate change wasn't happening. To do that, scientists have to rely on good statistical understanding of the normal climate system and weather — if warming weren’t happening — and make a clear distinction from what is actually happening now.

Collecting that historical data and building those scientific models has been difficult. But researchers have persisted. In 2018, a summer heat wave in northern Europe brought average temperatures more than 5°C higher (9° F) than the recent historical norm. Detailed studies of this event based on available data and atmospheric modeling eventually concluded that such an event was roughly 100 times more likely than it would have been in the absence of climate change. In a realistic statistical sense, climate change caused it, as well as the damage following from it, which included many hundreds of excess deaths caused by extreme temperatures in Sweden, Finland and Denmark.

The science for making such causal links has matured in the past decade due to concerted efforts of groups such as the World Weather Attribution organization, created by scientists who have developed exhaustive methods for determining which events are and aren’t good candidates for realistic attribution.

But it turns out that most of the cases brought against companies and governments so far haven’t been based on up-to-date attribution science. Plaintiffs’, in other words, haven’t been putting forth their best cases. And the real purpose of that Bloomberg article was to look at how this might change if parties damaged by climate change begin using the best science.

The good news is that better science is now being used and this, at least in part, has led to a huge surge in climate change-related cases. This trend could cause real pain for the corporations most responsible for greenhouse gas emissions — and for governments which have allowed them to continue emitting despite the growing consequences.

The article I’m working will be out in a week or so, I expect, and I can write more then. For now, I just thought I’d provide some links to some of the most important ongoing cases and some websites giving an overview of what is happening. Among the latter, I strongly recommend this website maintained by a number of researchers from the London School of Economics. As they note,

Globally, the cumulative number of climate change-related cases has more than doubled since 2015, bringing the total number of cases to over 2,000. Around one-quarter of these were filed between 2020 and 2022.

Things are definitely accelerating and both companies and governments are feeling the pressure.

Also, from the same group, this publication offers an overview of cases in Europe, which is currently the center of activity globally.

One of the most helpful contacts for me in exploring this topic has been Catherine Higham, a Policy Fellow at the LSE. She offered me a brief overview of some of the most important ongoing cases, each of which is important as it represents some particular case where an individual or group claims (plausibly in my view) to have been seriously harmed by the emissions of other parties, or the lack of action by governments. Of course, each case has its own particular details.

Among cases she mentioned:

Two parallel efforts have sought Advisory Opinions on the obligations of States under International law in recent weeks. This includes the filing of a request for an advisory opinion to the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea by the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and international law, which was established during COP26. A draft resolution requesting an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice has also been circulated at the UN General Assembly.

I don’t know much about Advisory Opinions, but they apparently can have significant impacts as precedents and could influence many future cases around the world.

Other trends mentioned by Catherine Higham (in her words):

Of around 50 cases filed in 2022 outside the US so far around 40% have been filed against corporate actors (including FIFA)

Many of these cases have concerned greenwashing and concerns that claims about carbon neutrality are not credible. This includes an important case filed against KLM filed in the Netherlands: https://climate-laws.org/geographies/netherlands/litigation_cases/fossielvrij-nl-v-klm.

In addition, a group of Indonesian residents from Pari have filed a case in Switzerland against cement company Holcim: https://climate-laws.org/geographies/switzerland/litigation_cases/four-islanders-of-pari-v-holcim. This case is interesting as it combines a number of strategies used in other cases requesting three different forms of relief: an order that the company must align its business model with the Paris targets, a contribution to adaptation costs, and compensation for loss and damage already suffered.

In the US, New Jersey became the latest state government to sue the fossil fuel industry, including the API. The case represents the continuing evolution of cases relying on US tort law, containing arguments focused on a failure to warn customers about the damage associated with the defendants products

All of which is, to me, slightly hopeful. The consequences of global warming are getting worse, and will continue to do so. Companies and governments seem to be digging in their heels, looking for ever more creative and dishonest ways to stick to business as usual. I hope, and many others hope, that the legal system may actually provide some real mechanism to bring pressure onto the companies and governments pushing future emissions.

If everything in the modern world seems to run around money, then perhaps money and monetary damages — or other related judicial decisions — may be the only pathway to real action. We can hope at least. And support the people around the globe who are bringing these cases. Good for them.